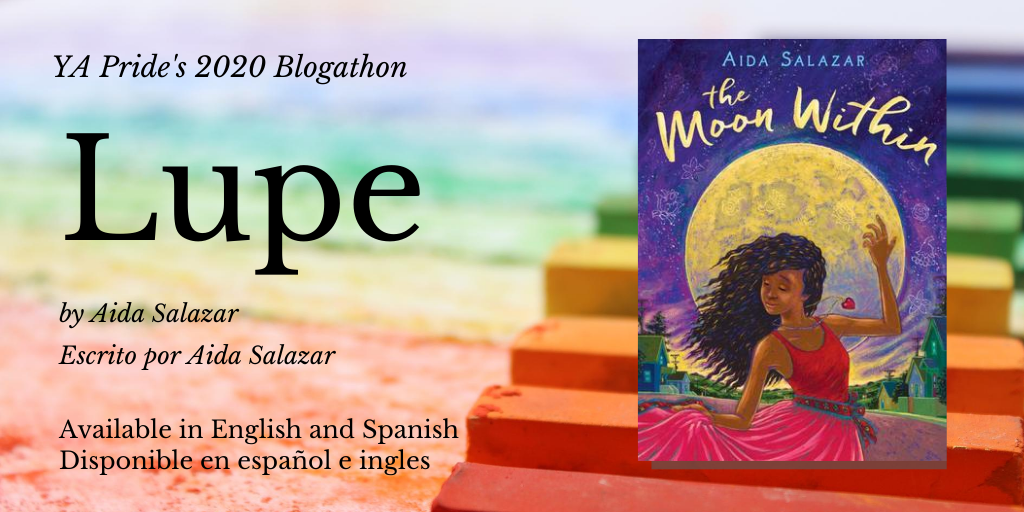

by Aida Salazar

I grew up watching impromptu drag shows in my living room. Many of my (very Mexican and straight) mother’s friends were men. They happened to be gay. Her best friend, Lupe, was like family. He and Mami knew each other from back in the pueblo when they were little and played dolls together. They both managed to find each other as immigrants in Southeast Los Angeles where they picked up right where they left off. Perhaps they were so close because Lupe’s strict Catholic family had disowned him and had even sent him to prison in Mexico for being gay but Mami never treated him differently because of who he loved. Mami grew closer to him in the US because her siblings were far away while Lupe only lived two blocks down. Whenever Mami would deliver a baby (and she had four more in the US), Lupe would come and cook for us and watch us so Mami could rest. He would also cut our hair, and scold us when we were out of line but also, he would shower us with so much love and adoration. Papi understood how close they were and never questioned their relationship. Lupe was family. That’s why it was not uncommon for Mami to have Lupe and his friends over for dinner, for enjoying music that blared from the old tape player, and for drinking rum and coke. They brought so much joy and freedom into our home and laughter, endless amounts of laughter. The drag shows were electrifying performances. Lupe and his friends had an instant audience with Mami, her seven children and sometimes Papi when he wasn’t working the night shift. They would emerge from Mami’s bedroom dressed in her clothes and makeup, singing and dancing and lighting up the room. They lip synced to Mexican pop songs and American ones as well though most of the men hardly spoke English. Through drag, they melted down any notion of rigidity around gender. I sat there happily among my siblings, cheering and paying witness to their brilliance, their magic, their freedom. Those were among the most grace-filled moments of my childhood.

At about six or seven years old, I wanted to be like my only brother. I wanted to wear my hair short like him, I wanted to wear jersey’s like him, I wanted to play football like him and be like just one of the guys. Mami did not bat an eye. She let me be who I wanted to be. The problem was not my immediate family per se, it was my extended Catholic family and friends at school who mocked me for being a “tomboy.” When I was in fifth grade, I gave in to their expectations and began to grow my hair longer and wear dresses again. I buried not only my gender expression but also my feelings of bisexuality down deep. The freedom that I experienced in my home was not as accepted on the outside. I learned then and as I grew that the world was actually cruel to folks whose genders or gender expressions were fluid or who were queer in any way and that some of our scariest opponents were Catholics and Christians in my own Latinx community.

When I wrote THE MOON WITHIN, the character Mar was inspired, in part, by my own experience as a child but also because of my study of Mesoamerican history. I noticed something interesting – the Mexica pantheon was filled with dual spirited deities and the principal deity, Ometeotl, was actually neither male or female but both, divine duality. Furthermore, I learned that people who were gender expansive or queer were often viewed through a sacred lens and often presided over spiritual ceremonies because they were a reflection of the creator. Also, through writer and scholar, David Bowles, I came to learn that there was a sweet name for gender expansive folks – xochihuah. It means those who bear flowers. For the Mexica, the flower symbolizes beauty and blossoming but also it symbolizes poetry. I like to think that a xochihuah is a person who carries poetry. How beautiful a concept but then how tragic we no longer have this knowledge and no longer practice it in our day to day lives. I wanted my intensely homophobic and transphobic community to remember these sacred understandings. Our indigenous religious practices had been stolen and erased through the brutality of colonization and the enforcement of Catholicism. These ancestral ways are proof that queer and gender expansive folks were once central to a spiritual practice in the Americas. In THE MOON WITHIN, I wanted to provide for us a model for how we could honor our gender expansive and queer loved ones through ceremony and spirituality instead of enacting the bigotry and hatred that Lupe experienced and that made me bury my own identity.

After THE MOON WITHIN was published, I could not share it with my queer friends and family who only spoke Spanish because it hadn’t been translated. One day, while at my mother’s house, her new friend Charlie, who happens to be a very talented drag queen, was visiting for breakfast. Charlie asked me, “Tell me the story of your book since I can’t read it for myself.” We sat there for over an hour as I tried my best to deliver the book scene by scene in Spanish. He was riveted. The only time he stopped me was to ask questions about our indigenous ancestry and how it all worked exactly. Though so much of our history has been lost, I did my best to offer him what I knew as I continued to share my story. It was amazing to witness how the story, coupled with this new information, spread a smile across his face. At first, he was filled with recognition, then illumination and ultimately, it turned to pride. “Ay, this is such a marvelous story! You don’t know how much I needed it.” Charlie reached to hug me and when I released, I saw the tears streaming down his cheeks. “Thank you,” he whispered. Then I started crying and Mami started crying and we folded into the biggest hug.

Though I wrote THE MOON WITHIN for children, I also wrote it in many ways to heal myself from the damaging narratives that have stripped us from understanding the spiritual power of menstruation and gender expansiveness. I wrote it to help others feel what I once felt as a child watching a drag show dismantle our binary notions of gender and be filled with the grace of freedom.

THE MOON WITHIN is now out in paperback. It was released in Spanish on June 2, 2020. You can purchase all editions at www.BooklandiaBox.com.

—

Aida Salazar is an award-winning author and arts activist whose writings for adults and children explore issues of identity and social justice. She is the author of the middle grade verse novels, THE MOON WITHIN (International Latino Book Award Winner), THE LAND OF THE CRANES (Fall, 2020), and the bio picture book JOVITA WORE PANTS: THE STORY OF A REVOLUTIONARY FIGHTER (Spring, 2021). All published by Scholastic. She is slated to co-edit with Yamile Saied Méndez, CALLING THE MOON: A middle grade anthology on menstruation by writers of color (Candlewick Press 2022). She is a founding member of Las Musas – a Latinx kidlit debut author collective. Her story, BY THE LIGHT OF THE MOON, was adapted into a ballet production by the Sonoma Conservatory of Dance and is the first Xicana-themed ballet in history. She lives with her family of artists in a teal house in Oakland, CA.

Aida Salazar is an award-winning author and arts activist whose writings for adults and children explore issues of identity and social justice. She is the author of the middle grade verse novels, THE MOON WITHIN (International Latino Book Award Winner), THE LAND OF THE CRANES (Fall, 2020), and the bio picture book JOVITA WORE PANTS: THE STORY OF A REVOLUTIONARY FIGHTER (Spring, 2021). All published by Scholastic. She is slated to co-edit with Yamile Saied Méndez, CALLING THE MOON: A middle grade anthology on menstruation by writers of color (Candlewick Press 2022). She is a founding member of Las Musas – a Latinx kidlit debut author collective. Her story, BY THE LIGHT OF THE MOON, was adapted into a ballet production by the Sonoma Conservatory of Dance and is the first Xicana-themed ballet in history. She lives with her family of artists in a teal house in Oakland, CA.

—

Escrito por Aida Salazar

Crecí viendo shows de drag improvisados en la sala de mi casa. Muchos de los amigos de mi madre (que a propósito es muy mexicana y heterosexual) eran hombres. Todos ellos eran gay. Su mejor amigo, Lupe, era como familia para nosotros. Él y Mami se conocían desde que vivían en el pueblo cuando eran pequeños y jugaban a las muñecas juntos. Ambos lograron encontrarse como inmigrantes en el sureste de Los Ángeles, donde retomaron su amistad justo donde lo dejaron. Tal vez eran tan unidos porque la estricta familia católica de Lupe lo había repudiado e incluso lo había mandado a la cárcel en México por ser gay, pero Mami nunca lo trató de manera diferente por quien el amaba. Mami se acercó a él en los EE. UU. Porque sus hermanos estaban muy lejos, mientras que Lupe solo vivía a dos cuadras. Cada vez que Mami daba a luz a un bebé (y tuvo cuatro más en los EE. UU.), Lupe venía a cocinar para nosotros y nos vigilaba para que Mami pudiera descansar. También nos cortaba el cabello y nos regañaba cuando estábamos fuera de lugar, pero también nos bañaba con tanto amor y adoración. Papi entendió lo cerca que estaban y nunca cuestionó su relación. Lupe era familia. Es por eso que no era raro que Mami invitara a Lupe y sus amigos a cenar, a disfrutar de la música que sonaba en el viejo tocadiscos y a beber ron y coca cola. Trajeron tanta alegría y libertad a nuestro hogar y risas, cantidades interminables de risas. Los shows de drag fueron actuaciones electrizantes. Lupe y sus amigos tenían una audiencia instantánea con Mami, sus siete hijos y, a veces, con Papi cuando no estaba trabajando en el turno de noche. Salían de la habitación de Mami vestidos con su ropa y maquillaje, cantando y bailando e iluminando la habitación. Cantaban canciones pop mexicanas y también estadounidenses, aunque la mayoría de los hombres apenas hablaban inglés. A través de su show, derritieron cualquier noción de rigidez en torno al género. Yo me sentaba allí felizmente entre mis hermanos, viéndolos y dando testimonio de su brillantez, su magia, su libertad. Esos fueron algunos de los momentos más llenos de gracia de mi infancia.

A los seis o siete años, quería ser como mi único hermano. Quería usar mi cabello corto como él, quería usar camisetas como él, quería jugar al fútbol como él y ser como uno de los muchachos. Mami no pestañeó. Ella me dejó ser quien quería ser. El problema no era mi familia inmediata tanto como mi familia católica extendida y mis amigos en la escuela que se burlaban de mí por ser una “marimacha”. Cuando estaba en quinto grado, cedí a sus expectativas y comencé a dejarme crecer el cabello y a volver a vestirme con faldas. Enterré no solo mi expresión de género sino también mis sentimientos de bisexualidad en el fondo. La libertad que experimenté en mi hogar no fue tan aceptada en el exterior. Entonces aprendí y, a medida que crecía, que el mundo era realmente cruel con las personas cuyos géneros o expresiones de género eran fluidas o que eran queer y que algunos de nuestros oponentes más temibles eran católicos y cristianos en mi propia comunidad latina.

Cuando escribí THE MOON WITHIN, el personaje de Mar se inspiró, en parte, en mi propia experiencia cuando era niña, pero también por mi estudio de la historia mesoamericana. Noté algo interesante: el panteón mexica estaba lleno de deidades de doble espíritu y la deidad principal, Ometeotl, en realidad no era ni masculina ni femenina, sino ambas, dualidad divina. Además, aprendí que las personas que eran expansivas en el género o queer a menudo eran vistas a través de una lente sagrada y a menudo presidían ceremonias espirituales porque eran un reflejo del creador. Además, a través del escritor y erudito, David Bowles, llegué a aprender que había un dulce nombre para la gente expansiva de género: xochihuah. Significa aquellos que llevan flores. Para los mexicas, la flor simboliza la belleza y el florecimiento, pero también simboliza la poesía. Me gusta pensar que un xochihuah es una persona que lleva poesía. Qué concepto tan hermoso, pero qué trágico que ya no tenemos este conocimiento y ya no lo practicamos en nuestra vida cotidiana. Quería que mi comunidad intensamente homofóbica y transfóbica recordara estos entendimientos sagrados. Nuestras prácticas religiosas indígenas habían sido robadas y borradas a través de la brutalidad de la colonización y la aplicación del catolicismo. Estas formas ancestrales son prueba de que las personas queer y de género expansivo alguna vez fueron centrales para una práctica espiritual en las Américas. En THE MOON WITHIN, quería proporcionarnos un modelo de cómo podríamos honrar a nuestros seres queridos trans y queer a través de la ceremonia y la espiritualidad en lugar de representar la intolerancia y el odio que Lupe experimentó y que me hizo enterrar mi propia identidad.

Después de que se publicó THE MOON WITHIN, no pude compartirlo con mis amigos y familiares queer que solo hablaban español porque no había sido traducido. Un día, mientras estaba en la casa de mi madre, su nuevo amigo Charlie, que resulta ser una drag queen muy talentoso, estaba de visita para el desayuno. Charlie me preguntó: “Cuéntame la historia de tu libro, ya que no puedo leerlo por mí mismo”. Nos sentamos allí durante más de una hora mientras hacía todo lo posible para relatar el libro escena por escena en español. Estaba clavado. La única vez que me detuvo fue para hacer preguntas sobre nuestra ascendencia indígena y cómo funcionaba todo exactamente. Aunque gran parte de nuestra historia se ha perdido, hice todo lo posible para ofrecerle lo que sabía mientras continuaba compartiendo mi historia. Fue sorprendente ver cómo la historia, junto con esta nueva información, extendió una sonrisa sobre su rostro. Al principio, se llenó de reconocimiento, luego de iluminación y, finalmente, se convirtió en orgullo. “¡Ay, esta es una historia tan maravillosa! No sabes cuánto lo necesitaba “. Charlie extendió los brazos para abrazarme y cuando lo solté, vi las lágrimas corriendo por sus mejillas. “Gracias”, susurró. Entonces comencé a llorar y Mami comenzó a llorar y nos envolvimos en un abrazo grandísimo.

Aunque escribí THE MOON WITHIN para niños, también lo escribí en parte mayor para curarme de las narrativas dañinas que nos han negado la habilidad de comprender el poder espiritual de la menstruación y la expansión del género. Lo escribí para ayudar a otros a sentir lo que una vez sentí cuando era niña al ver un espectáculo de drag desmantelar nuestras nociones binarias de género y estar llenos de la gracia de la libertad.

THE MOON WITHIN ahora está la venta. Se lanzará en español LA LUNA DENTRO DE MI el 2 de junio de 2020 y se celebrará con un evento de lanzamiento de libros en línea el 4 de junio. Puede comprar todas las ediciones e inscribirse para asistir al lanzamiento del libro en https://booklandiabox.com/pages/events